Oof. Do you remember the end of 2020, when it looked like there was a light at the end of the tunnel. Who would have said it was an incoming train?

Anyway, video games. Another year, another recap of my year in game design. What caught my attention? What will I associate with this year?

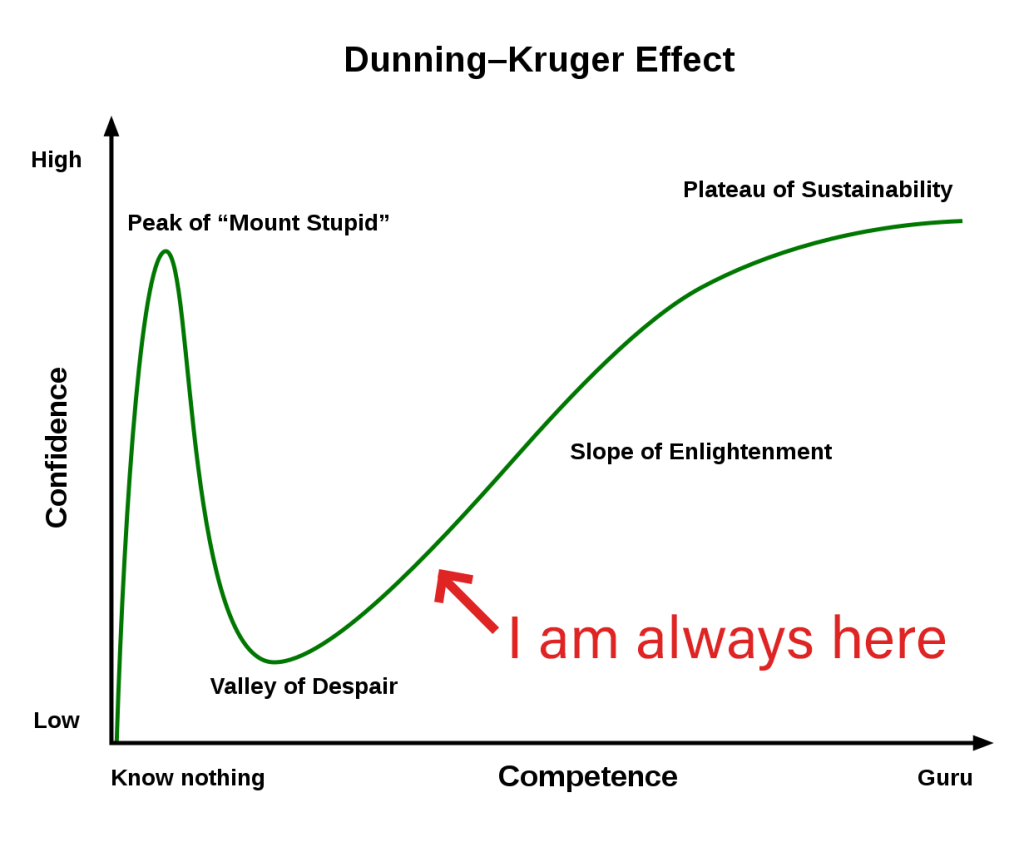

First of all: I played A LOT of games. The more I get into this career, the more curious I get about games. I always say that I love game design because I can’t see the ceiling: every time I feel like something truly excellent has been made, something I can aspire to reach one day, a new excellent peak comes. It’s like always being near the valley of despair of the Dunning Kruger curve.

Except, you know, it’s exciting. The day I will feel like I truly know what I am doing, I will probably look for another job.

Incidentally, this coming year will mark my first decade in game making. I had worked in the game industry before in QA and marketing (and even before working directly in the game industry I had a good decade as a game journalist – god I am old), but I first started making games as a game designer ten years ago, when my friend Simone convinced me to create a company and work on our first game, what would become Derat Inc. Shockingly, we made that game in less than six months. Maybe the overconfidence of beginners is a good thing.

Things I actually did

Let’s start: the first thing that attracted most of my attention and effort is the thing I can say the least about. In my day job I had the chance to think about really hard design problems, do a lot of different things, learn from ridiculously talented people, still bump my head into the same hard design problems, do more cool things and so on and so on. I can’t really say much, but I can link to what a colleague wrote and you can extrapolate and read between the lines.

On the personal side, the only solo project I did was once again in Dreams. It was a level for the Megapenguin Rehatched project, a game made by Media Molecule together with the Dreams community. Considering how awfully busy – and just plain awful – this year was, I felt one single level – although with some custom mechanics – was as much as I could realistically make. I am very proud of the result. Here you can see the lovely people at Media Molecule playing my level and say nice things about it:

https://www.twitch.tv/videos/1131116306?t=00h37m31s

After that I decided to take some time off Dreams and got back to my old object of hate/love, Unity. I love making things in Dreams, and I love how relatively easy it is to make something that looks good and plays good, but I got the itch to explore a concept that has been in my mind for years and that would really not fit with an engine like Dreams. Whether it will become something concrete is unknown. Come back in a year (hopefully) to see if anything happened.

Things I played

As I said, I played A TON of games this year. I like most of them and I am slowly learning to abandon the ones that do not click with me. I am a completionist by nature, so that is not something that comes natural to me. I am working on it. So… I won’t talk about the many games I liked – Returnal, Deathloop, Metroid Dread, It Takes Two – but about which I really I have no particular insight. I will instead talk about the games that were personally special for me and/or that were a source of inspiration as a game designer.

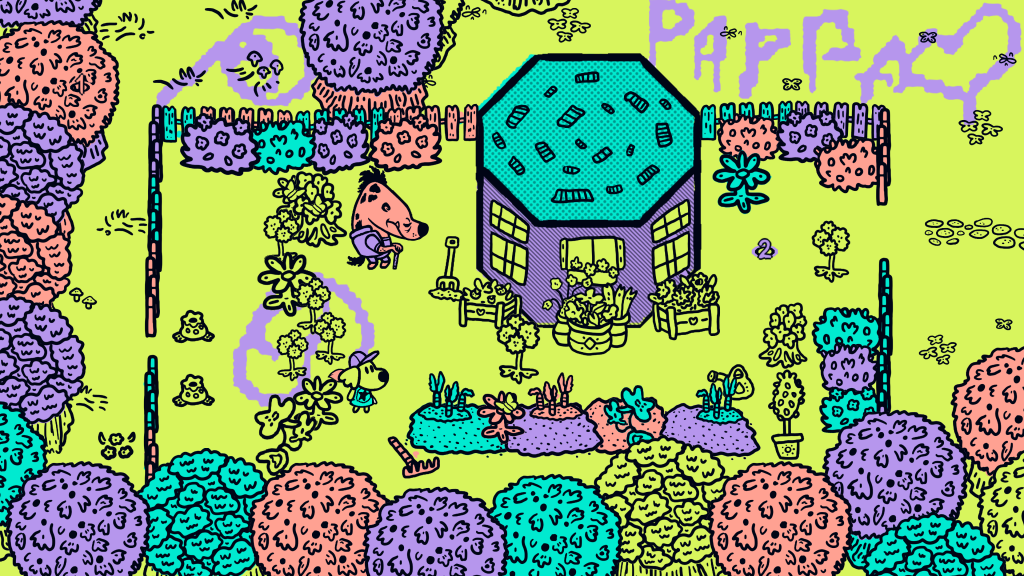

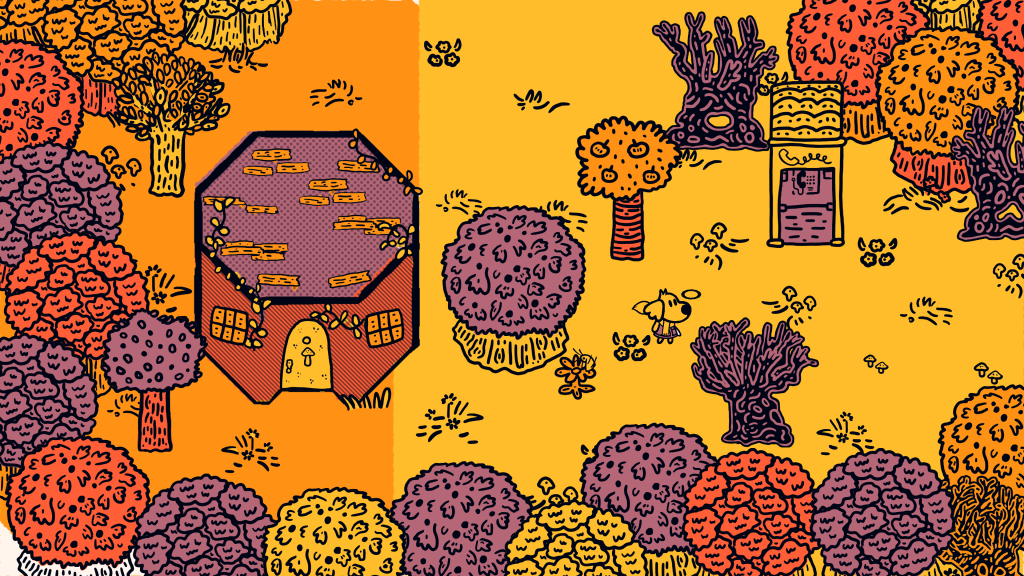

Chicory: A Colorful Tale

What a delightful experience! I played this game with my 9 years old daughter and it was, by far, my best gaming experience of the year. Chicory is, at its core, a 2D Zelda-like adventure based on the possibility to paint anywhere on the screen, and using the act of painting to solve puzzles and progress.

Although it is essentially a single player experience, the game does have a pretty simple multiplayer mode in which a second player controls an extra paint brush. It is a case of a secondary, small feature allowing a play experience that would otherwise not exist. While I controlled the main character and one brush, my daughter controlled the secondary brush. It may seem like a very lopsided 2-player mode, one in which only one player has agency by controlling the protagonist, and yet it felt like we played together, in the deepest sense of the word. How much a player spends making the environment pretty vs just painting to progress is up to the player. This makes the 2 player mode incredibly accessible – as the second player only needs to use one stick and two buttons – while still making player 2 relevant for one of the most important part of the design, the creative one. You may not control the main character, but you can control how the world looks like (and help the main character to progress as well).

As I said, we truly played together: while playing, me and my daughter constantly chatted about the best palettes of colors, about the best way to color a mountain and which colors are acceptable for a river. We screamed at boss fights, we laughed at some characters and dialogue, we cheered when we found a well-hidden collectible.

And we also talked about depression, about expectations, self expression and doubt (Chicory deals with some dark themes, although never in a morbid way) . Finally, we enjoyed some of the best game music and art style of the year.

I don’t know if Chicory would have had the same impact if I played it on my own. I would have liked it for sure. But playing it with my daughter made it one of the most memorable gaming experiences of my life.

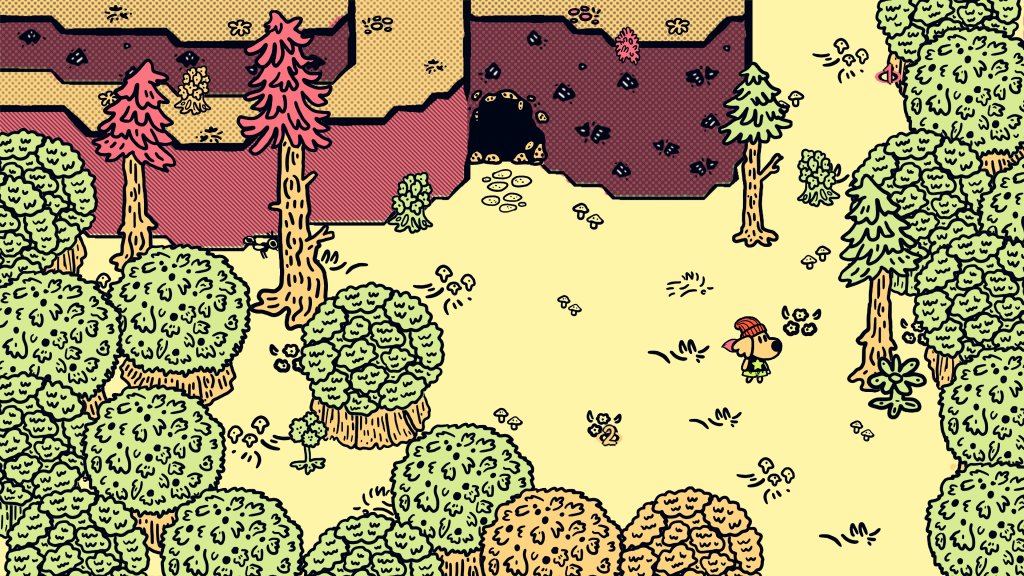

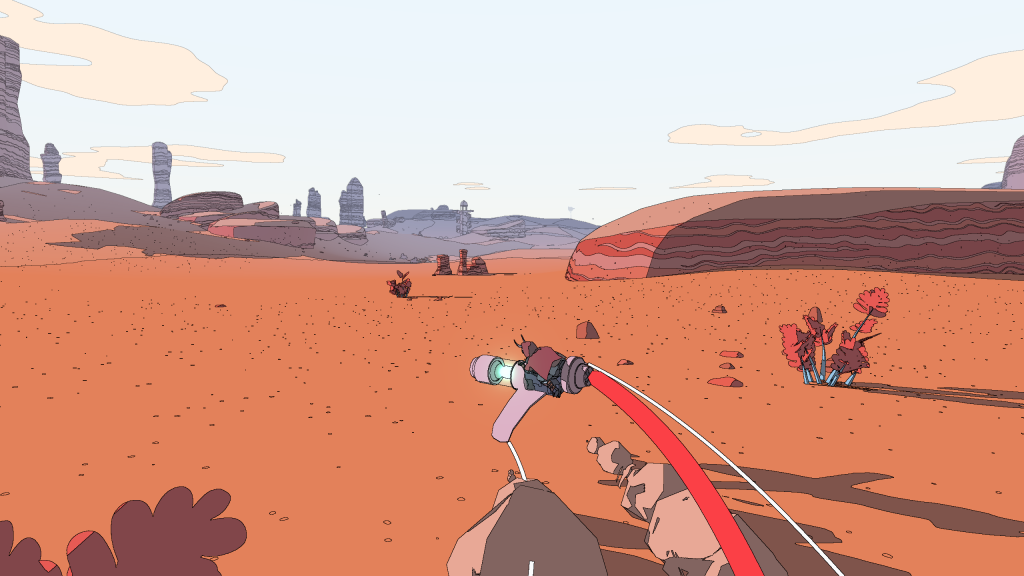

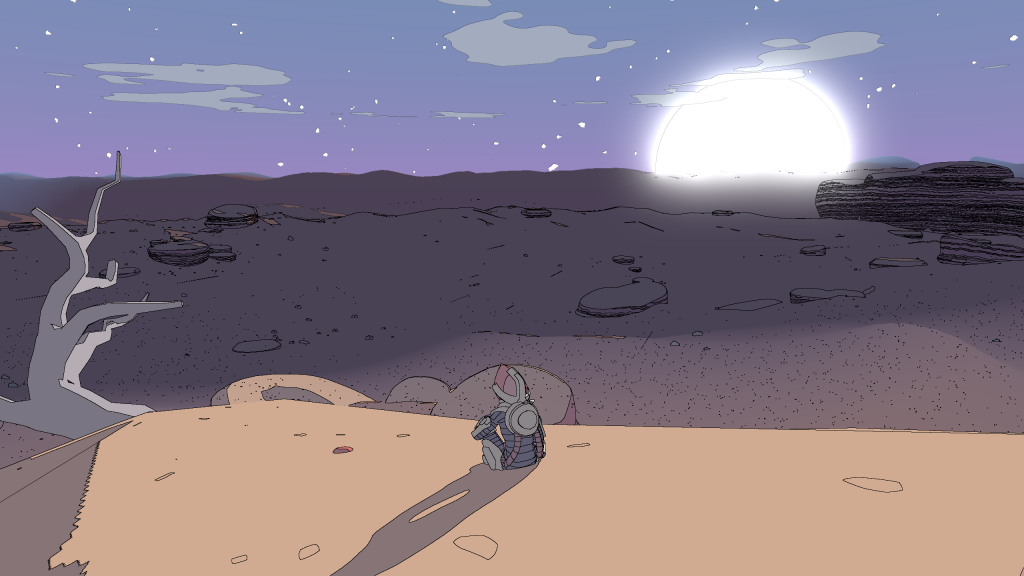

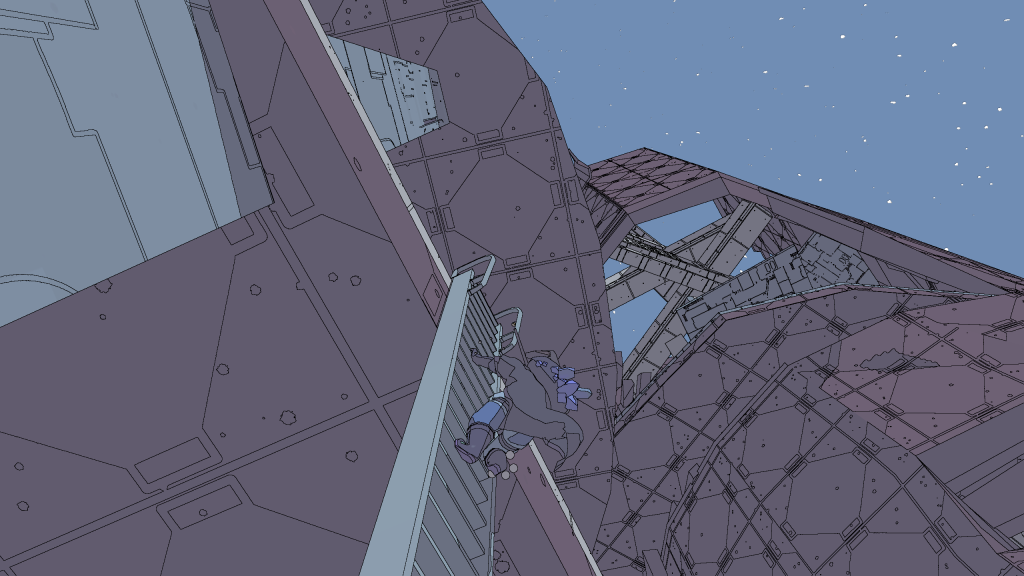

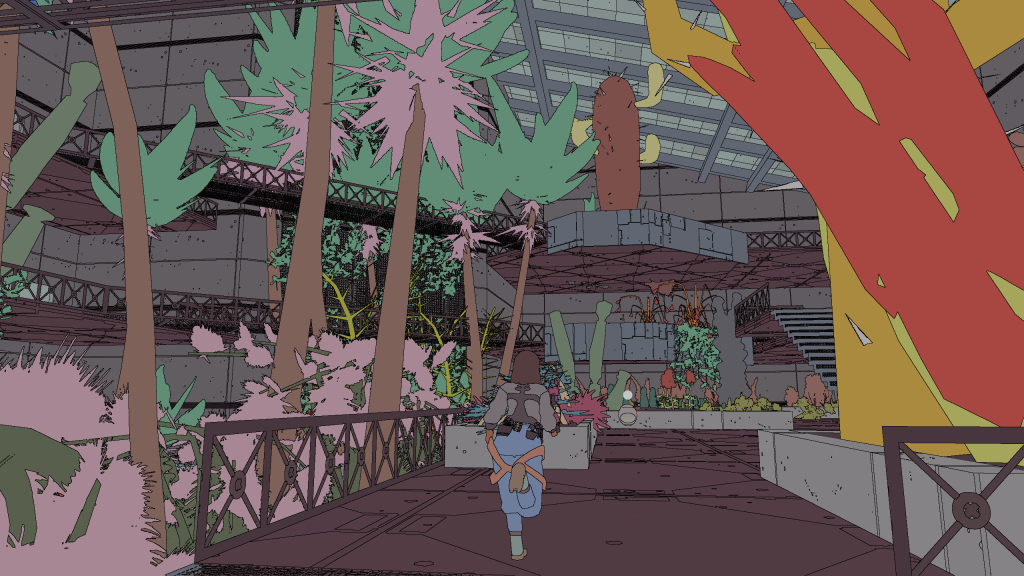

Sable

Back in 2017, as I got to the end of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, I realized a couple of things. The first one is that it would be a while before I would play something this good again. The second one was that from that point on, open world games would never be the same. The first prediction might have become true: I still haven’t played something quite as brilliant. The second one is more complicated. Perhaps development periods are so long these days that it will be a while before we see the true impact of BotW on open world design. Or maybe the formula is even harder than it looks to replicate. But regardless, many games cited BotW as an inspiration, and none of them managed to capture what really made BotW special. Sable is the first one to get really close.

Sable is one of those games that it’s a 7 out of 10 for 80% of people, and a 9 out of 10 for 20%. Needless to say, I am in that 20%. The thing is that Sable, for all its bugs and its over-reaching, is probably the first game that captures that unique exploration experience of Zelda.

The story is as low stakes as it gets: there is no global emergency to solve, the world is fine, and the only conflict is about the protagonist having to decide what she will be in her future life. Your mission is to go out in the world and decide what you want to be. This setup implicitly gives the player the freedom to take all the time, explore, look around, discover the history of this alien world, or just hunt for collectibles.

Sable shows the confidence of every game that dares to be truly minimalist. There is no combat, no ability progression – apart from stamina, that determines how high can you climb – and not even a real difference between primary quest and subquests: the subquests ARE the quest. The game trusts the player will find a way and will find what the game has to offer, without artificial incentives. In an open world game, it feels almost revolutionary.

This stripped down gameplay, together with the gorgeous art direction and music, made Sable one of the games of the year for me. I just couldn’t stop playing. I wanted to explore that giant spaceship stranded in the horizon; I wanted to see if I could get to the top of that monolith, I wanted to find more ways to personalize my hoverbike.

Breath of the Wild created a new kind of sandbox experience, and we still haven’t seen the real consequences of that shift. Sable is the first example of what the future of open world design is.

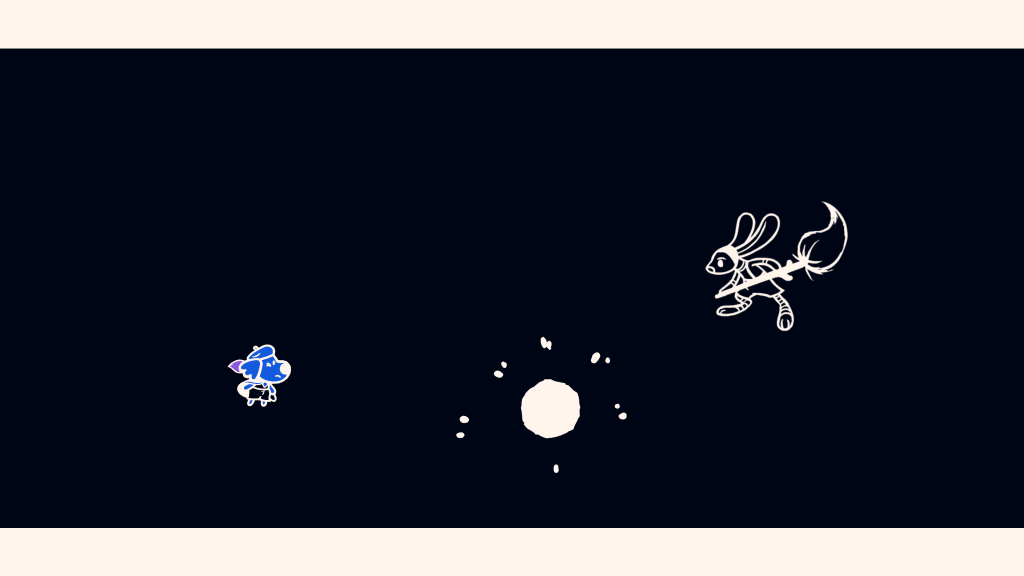

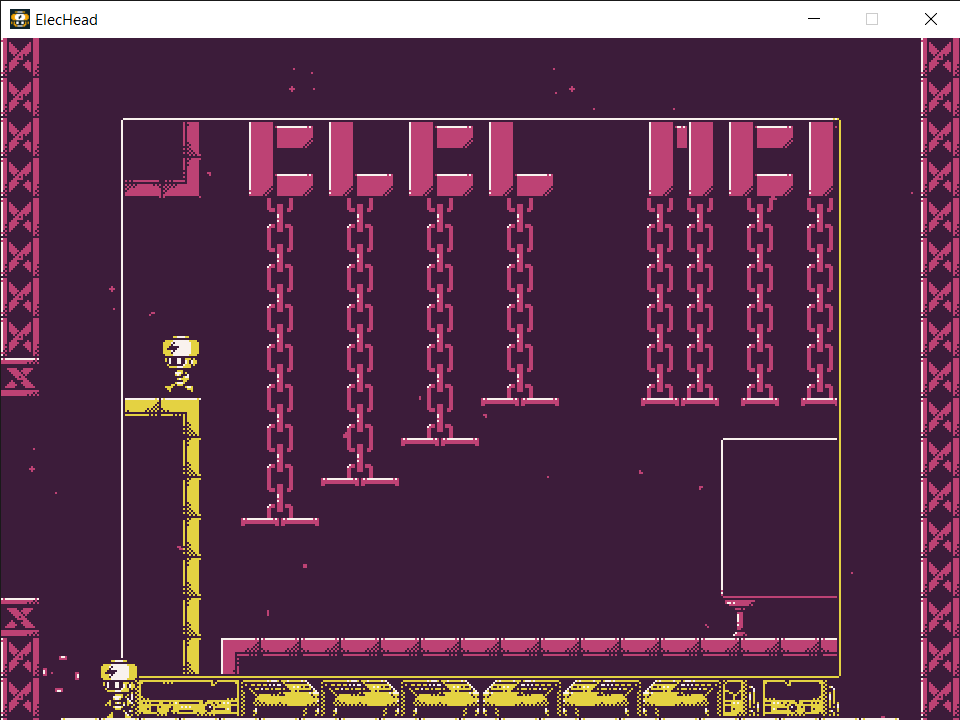

ElecHead

If Sable is all about the mix of stripped down system design and holistic world building, ElecHead is a hymn to focused content design. It’s a puzzle game based on a premise that, as good as it is, you could find in many game jam experiments, or countless indie games: your character generates electricity, so when you’re in contact with a conductive surface, you will be able to power up different mechanisms by touching that surface. It is a simple premise, and in the hands of the average game designer, it could have resulted in yet another puzzle platformer.

But ElecHead transcends that fate with pure, unadulterated, raw quality: the level design is so tight, the puzzles so well designed that it makes it one of the most compelling experiences of the year. Almost every single screen of ElecHead provides that elusive ha-ha moment that only the best puzzle games provide. Every level spins the basic properties of the character abilities in ways that you wouldn’t have imagined and yet seem so evident a posteriori. I played it all in two or three sessions, but what a pleasure it was.

ElecHead is proof that level design can really make or break a game. In that sense, it reminded me of Fez. And to me that is the biggest compliment I can give to a puzzle platformer.

Animal Crossing

It sounds like cheating. I already put Animal Crossing into last year’s round up. And yet, the 2.0 update and the Happy Home Paradise bumped the original New Horizons into the best of 2021 as well.

In a superficial way, for a game like Animal Crossing, quantity is quality. An update that introduces thousands of new objects, new features and improvements will inevitably make the game better and it will make it feel fresh. But, at a deeper level, the new update and expansion really make Animal Crossing the game it was supposed to be. And this is what I realized putting other dozens of hours into Animal Crossing: New Horizons during 2021: Animal Crossing is a game about beauty, work and love.

Beauty is probably the most important factor in Animal Crossing. The game seldom asks the player to do something because of a direct reward. In fact, the extrinsic motivation of Animal Crossing is as stripped down as it can reasonably be. You get new objects and currency for what you do in the game. But the real reward when you create a new home for a character, or when you finally get the missing piece of furniture you were looking for, is the aesthetic pleasure of imparting your style into a virtual environment. In other words, the reward is beauty itself. I feel that, as game designers, we often forget the power of aesthetics. Beauty is, and should be treated as, an end in itself. But beauty, in a vacuum, doesn’t feel so good unless it is earned. And here’s where work, the second element, comes in.

Those who complain about how “time consuming” changing the island layout, crafting items or decorating is are missing a key point: it is supposed to feel like that. We tend to thing about friction as something to avoid at all costs. In most cases, that it true. But Animal Crossing without friction would be a fundamentally different experience, and probably not a better one. The fantasy of the “simple life” at the core of Animal Crossing relies on work because work is what humans are supposed to do. I am not talking about salaried work – though in some cases, sometimes, for some fortunate people, the two things align – but the concept of work as productive activity that benefits someone. Animal Crossing is about that: the toil that produces an aesthetically pleasing, functional result.

The final element is love. Animal Crossing is shamelessly about love. Love for the people around you, whether it is your family sharing your same island on the same Switch, or the villagers that populate your island. It is about connection, about chitchat, about small presents and small acts of kindness.

Sigmund Freud said that “Love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness”. He forgot “beauty”, but only because he was a grumpy old Austrian man. Otherwise, he was pretty much spot on.

Ultimate NES Remix

If you managed to suffer my ramblings up until now, you will allow a little exception to the rule: this is not about a game released in 2021. It’s about a 3DS game from 2014, built on games from the ’80s. And yet I feel it’s incredibly relevant in 2021. Let me explain.

The NES Remix series takes bits and pieces of classic NES games and wraps them as micro-challenges: collect 15 coins in this Super Mario Bros level as fast as you can; beat this Punch Out enemy with an uppercut; find the exit in this Zelda II screen, and so on. It takes familiar gameplay and breaks it down in 15 seconds challenges. For many different reasons, the problem of how to turn simple elements into compelling challenges has been in my mind A LOT during this year.

I dug deep into Ultimate NES Remix because I feel it is a brilliant lesson on how to take classic gameplay and build something fresh out of it. Maybe you would not find a whole match of the original Mario Bros compelling. But, as a time attack challenge, the old formula feels suddenly new. Now it’s all about find the most efficient movement, the perfectly executed jump, the unexpected acrobatic maneuver that cuts a couple of seconds. Speedrunners, of course, know about the very special appeal of this mindset. But speedrunning also has, by design, an immense difficulty curve; the investment of time and energy is astounding. The NES Remix series makes it accessible.

During 2021 I went back to a lot of DS and 3DS games I overlooked in the past, and it was a fantastic journey. Of all the games I got and played, Ultimate NES Remix was the hidden gem that gave me a lot of inspiration for my everyday work as a game designer. I still hope that Nintendo will at some point revive the series and make new installments, maybe with games from other consoles. It seems like it would be a great addition to their online service. A fan can hope.

Final words

As challenging as a year it was, I can’t deny that I spent 2021 doing what I love. I am immensely privileged and lucky. I love what I do and I feel making games is the most noble of occupations. So here’s to another year of games.

Have fun.

PS: album of the year was St. Vincent’s Daddy’s Home. Novel of the year was Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. Movie of the year is still TBD: I didn’t feel it was ok to go to the cinema, the backlog is big and so it will be a while before I can watch all the 2021 movies I want to watch.