Sometimes the old itch to write comes back and the end of the year is always a good time to make lists and retrospectives. So, I decided to write one on what happened in the world of game design during 2020.

There is pretty much nothing here on what I do during my day job as game designer. On that front, it has been a very rich year, with high highs and low lows, and it saw me changing jobs and getting onboard a fantastic project with huge potential. Hopefully I will be able to talk about that one day. For now, these are the things, ideas and trends related to game design that defined the year that just passed for me. It is highly subjective and completely arbitrary, just so you know.

Videogames outside the screen

I never liked the argument that games are useful because you can use games to push people to do something, teach them, or motivate them. A game that is just fun is already a miracle, and making people smile is one of the most noble and worthy things that a person can do. Having said that, Ringfit Adventure improved the life of a lot of people, mine included. In one of the worst years in recent history (and let’s just hope 2020 remains an exception) this game helped a lot of people to maintain their physical and mental health. Which is why it’s here even though it released in 2019.

We have seen plenty of fitness games before but, unlike those, Ringfit Adventure is not trying to look like something else. On the contrary, it is unapologetically a game. A lightweight RPG, but still a game. And being a game doesn’t prevent it from being an excellent fitness routine. A progressive, smart, balanced and good fitness routine, one that takes away the toxicity from working out and focuses and the real point of fitness. Ringfit Adventure is not about getting swole or losing weight. It’s about feeling good with your body and training it to become stronger, more balanced and more flexible. And, sure, it will help you lose weight and get some muscles. But it’s not the primary focus.

Again from Nintendo – this will be a recurring theme, I am afraid – Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit took Mario Kart out of the screen and in the living room. Nintendo is famous for using established technology to do new things with it, and Mario Kart Live is the latest example of Nintendo teaching a new trick to an old dog: an AR-enhanced game where you can drive a small RC car in your home. The miracle here is that it feels like Mario Kart. Even the most physics-defying feature of Mario Kart, the drift-to-get-a-boost move, is here. I am still unsure how the hell that actually works, but it feels right. And the perception of speed is incredible, even when you realize the actual speed of the toy car is not that great. In a normal year I would have started to organize office competitions. In the year of work from home, I accept that the best I can do is beat my own best time on the track I built, and that has to be enough. I wish I could say my kids where as excited as I am about it, but they really didn’t love it. Insert old man rant about kids these days.

The year of social games. No, really.

It may be a cliché at this point: Animal Crossing: New Horizons was the game of the pandemic and, by extension, of 2020. My first and most loved AC game will always be the original on Gamecube, but one thing that New Horizons reminded me about is that there is a lot of value in all those elements that we, as designers, often overlook. The pleasure of New Horizons is not only and not so much in the features and mechanics. Of course, at the core of every Animal Crossing game there’s a fairly sophisticated progression, collection and economy setup, and that’s what hooks players first. But what makes them stay is much more immaterial. It’s all the light mechanics about player expression, it’s the gestures, the cosmetic content, the absurdly big amount of lines that characters can say. That huge amount of content and features that have expressive value – with little or no mechanical consequence – is why people love Animal Crossing, and it’s what makes it the best social game in modern time.

Player self expression works in an interesting way, in Animal Crossing. The tools that players have to show their creativity are not particularly deep: you cannot model your own furniture, you cannot decide to place object at any angle, you cannot customize every part of your character and so on. But they are wide. There is so much content that players have found countless ways to create, arrange and show their personality. And this is what makes this game so incredibly social: me and my kids would talk so much about the different personalities of the characters in our island, or argue about island decorations. They quite soon started having small parts of our island dedicated to a specific purpose: they made little “stores” and gyms and spas that they would then show me. It is a social gameplay loop that is so much more rewarding and real and engaging than any “social game” I have seen.

Another social gaming feature of my gaming 2020 was in the oldest way a game can be social: multiplayer. In particular, coop. This was the first year in which my children had enough confidence with games that I could play with them on a somewhat equal basis. Playing Fortnite on split screen on a PS4 and with an extra player on the Switch is still an absolute blast. I still have a certain resentment for how Fortnite weaponizes fear of missing out against children, but it’s impossible to deny that, at its core, the game is a lot of fun.

In a similar way, Sackboy: A Big Adventure turned out to be an unexpected little masterpiece. As a multiplayer coop experience, it gets so close to a golden Nintendo standard with new ideas introduced in pretty much every level and a difficulty level that hits the right spot for both experienced and less skilled players. And you can slap the other players, which is always hilarious.

Everything’s emergent

This is pretty subtle, and it has been going on for a number of years. However, I think that never like in 2020 it has been clear that emergent games are the future. When I say “emergent”, I mean it in the Jesper Juul’s “games of emergence vs games of progression” sense. In other words, we see fewer and fewer linear games, and even the ones that are linear try to give the player as much agency as possible.

Animal Crossing New Horizions is of course a prime example, but Roblox, Fortnite and, to be honest, most of the games in any monthly sales chart are part of this category. I found two examples of this trend particularly interesting.

The first one is Hades. Like many other roguelikes, Hades is strongly based on the surprising effects you get when you combine together different systems and mechanics (emergence in a nutshell). Unlike most other roguelikes, Hades applies that logic to its narrative as well. And so you get a very compelling puzzle where narrative bits slowly uncover a bigger picture, and those narrative bits depend on what you do during gameplay. I really hope to see this kind of narrative system applied widely. I think, for example, that it could be a great way of injecting meaningful narrative in multiplayer games.

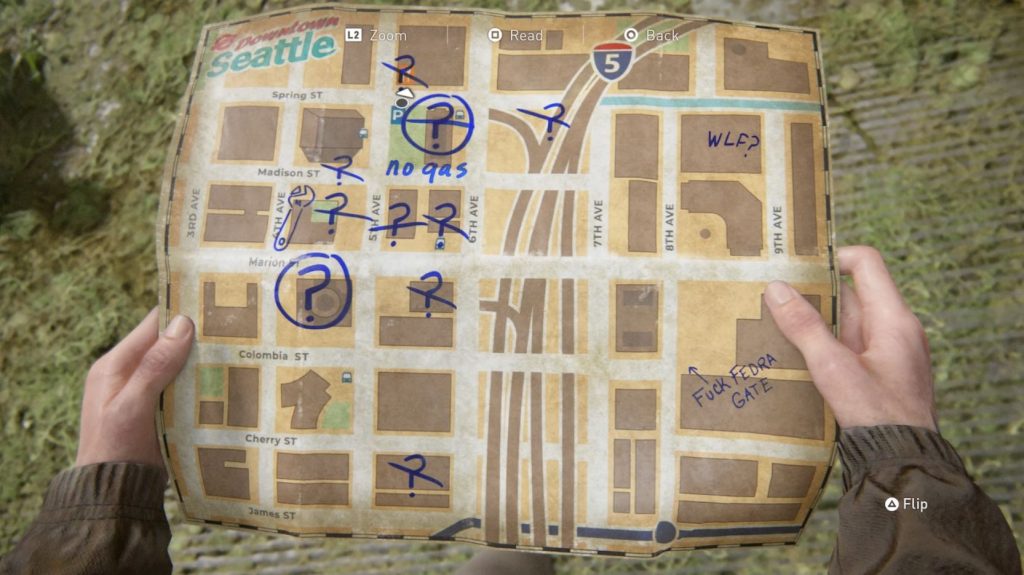

The other example of how emergence has taken over videogames is more unexpected. Many would say that the very clearly defined narrative of The Last of Us Part 2 is a prime example of linearity typical of a game of progression. Outside its story, though, TLoU2 does some pretty incredible things with its emergent gameplay systems. First of all, it has one of the best enemy AI systems ever. Enemies in TLoU2 are at the same time challenging, believable, emotionally interesting and fun to fight. And that’s a monumental achievement. But even beyond AI, TLoU2 is the best stealth and combat sandbox since Metal Gear Solid 5. It introduces large areas and still manages to create the anxiety-inducing and exhilarating feeling of being in great danger while barely surviving. That feeling of improvising during combat, thinking quickly and making plans just to get rid of the next enemy is something Naughty Dog are masters at creating, and it’s never being as well realized as in The Last of Us Part 2.

Also, Abby rules.

Sense, touch and feel

Finally, what occupied a big portion of the game design part of my brain this year was game feel. It’s nothing new, really: I often say that game feel is 50% of the fun in games (another 25% is audio). However, three things in this area kept my attention in 2020.

The first one is PlayStation 5’s Dual Sense and its implementation in Astro’s Playroom. There has been a lot of talk about how the new PlayStation controller can give the tactile feeling of surfaces being walked on, weather effects or different resistance in its triggers so I am not going too in-depth in recapping it. What I am actually incredibly eager to see is what other developers will do, because I genuinely think it could be a game changer for a lot of games (looking at you, Ratchet & Clank). The importance of rumble and sound effects is often underrated, so I really want to see more developers taking the Dual Sense haptic feedback one step forward.

The second thing that got my attention was A Short Hike. Apart from being a delightful experience (more games like this, please!), A Short Hike is a great example of the power of game feel. Everything in this game is more rich, pleasant and fun to interact with that it has any right to be. Moving is fun – and faster than I would expect in such a game -, flying and jumping and climbing are all absurdly satisfying. We, as game designers, tend to think way too much about mechanics and systems and not enough about the subtlety of interactions, and A Short Hike is proof that they can make or break a game.

Speaking of which, the last thing (and my only personal project this year) was an exploration on these detail-oriented design decisions. I spoke more in depth about the making of Pancakes? Pancakes!, a game inspired by Game & Watch games I made using Dreams, in a previous post. It took a good chunk of my free time, and I have to say that it has been refreshing to put so much thought and effort in a game of such small scope. It allowed me to really focus on game feel and presentation and I am pretty proud of the final result.

To close up this thing: 2020 was a pretty good year, if seen through the lens of game design. I got to work on some very cool things, I played a lot of good games, and I taught two Advanced Game Design courses at the Futuregames school here in Stockholm. This last experience, especially, has been an absolute pleasure. I loved working on lectures, interacting with students and seeing their projects take shape. It’s definitely something I want to do again and I learned so much doing it: it may be a cliché, but it’s true that in order to really know something you should try to teach it. So at least something good came out of this garbage year.

Now let’s hope for a better 2021.